e-book price is $80

I'll get it through Inter-Library Loan for free. Order Request put in to my local library as pickup.

This book presents a critical evaluation of the doctrine of the Trinity,

tracing its development and investigating the intellectual,

philosophical and theological background that shaped this influential

doctrine of Christianity. Despite the centrality of Trinitarian thought

to Christianity and its importance as one of the fundamental tenets that

differentiates Christianity from Judaism and Islam, the doctrine is not

fully formulated in the canon of Christian scriptural texts. Instead,

it evolved through the conflation of selective pieces of scripture with

the philosophical and religious ideas of ancient Hellenistic milieu.

Marian Hillar analyzes the development of Trinitarian thought during the

formative years of Christianity from its roots in ancient Greek

philosophical concepts and religious thinking in the Mediterranean

region. He identifies several important sources of Trinitarian thought

heretofore largely ignored by scholars, including the Greek

middle-Platonic philosophical writings of Numenius and Egyptian

metaphysical writings and monuments representing divinity as a triune

entity.

youtube discussion of the book

Why

is this account of the development of doctrine from the Logos to the

Trinity so critically important in our time? Because the public, as

well as scholars, seems largely ignorant of the profound shifts in

thinking which occurred when the essentially Jewish faith of New

Testament times became severed from its roots and succumbed to the

distorting influence of neo-Platonism. The churches have in general

turned a blind eye to the somewhat embarrassing fact that a very strong

pagan Greek influence adversely affected the Christian faith as it

emerged after apostolic times.

Marian

Hillar is perhaps the first to put his finger on the detail of just how

Biblical Christianity's decline into a philosophical form of religion

came about. He shows us that the middle-Platonist Numenius quite

evidently exhibits an extraordinary affinity with the thinking of the

second-century Christian apologist, Justin Martyr. The mid-second

century marks the transition, via a mishandling of John's logos

teaching, from one theological paradigm to a new and very different one.

By stages the unitary monotheism of Jesus and the apostles became the

complex construction of the nature of God as Trinity. Now that this

scholar has laid bare the evidence, we are all more able to reevaluate

our own positions vis-a-vis Christianity as it originally stemmed from

Jesus himself.

Marian Hillar's book on Restoring the Lost Logos and how Christianity got corrupted by Platonism

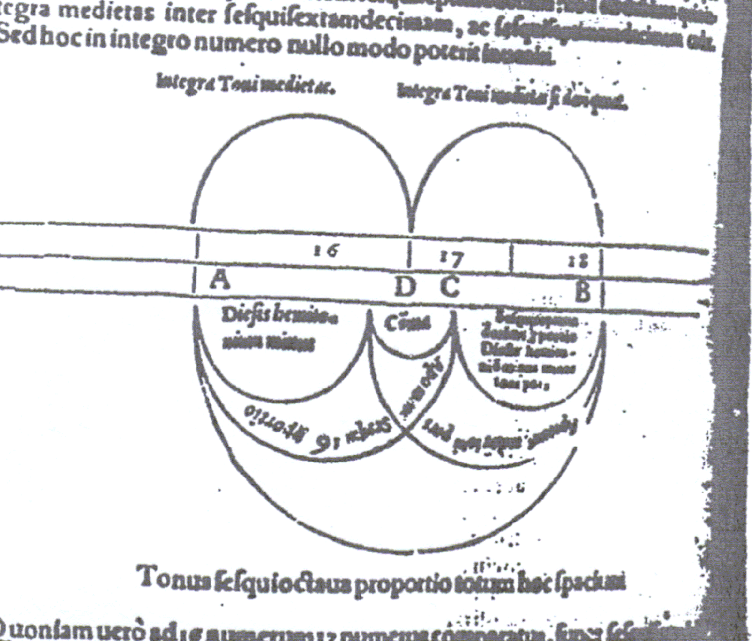

Building

on this ubiquitous understanding, Pythagoras (570 b. c. e), a noted

theologian and philosopher, taught the “cosmological principles, Monad,

Dyad and Harmony” (7). Hillar labels this a “trinity” which corresponds

to the moral philosophy of Goodness, Truth and Beauty. (10). Men of

that era believed these principles controlled the Universe and were a

“philosophy of immanent order” (8).

Hillar next discusses several

philosophers who added concepts to the accepted philosophical thought on

Logos. Among them was Alemaeon of Croton, who mingled the idea of

Logos with medicine, thereby setting the precedent for the development

of the Hippocratic Oath (9,10). Other early disciples included

Heraclitus of Ephesus who equated “Mind” with Logos by discussing the

force of Logos/Mind in creation, and Anaxagoras of Clazomenae who

thought “Mind” more an impersonal force (11).

The philosopher,

Xenocrates of Chalcedon (d. 314 b. c. e.), agreed with Pythagoras and

Plato that numbers represent universal regularities and melded “the

ideal with the mathematical” (22). And, “Xenocrates philosophy

constitutes an important transition to Middle Platonism” (22).

Xenocrates discussed the ideal in terms of the three perfect triangles:

equilateral, representing unity; isosceles, representing unity and

variety; and scalene representing “descending souls with material

elements” (23), i. e., human beings.

Adding to this foundation, the

Stoics of the third century b. c. e. developed the thought on Logos

which became the accepted teaching of early Christians. The Stoics

taught that the principle of Logos governed the structure of the world.

It was a “celestial fire, intelligent breath” (26). They believed

several “world cycles began and ended with fire” (31), and that warm,

intelligent breath, pneuma, held the elements of the universe together.

The

equivalent Hebrew concept of Logos, davar, was considered to be “the

speech of God”. It is often seen in the Old Testament as “And God

said,” (36). From this Hillar directs the reader in a discussion of the

Hebrew personification of Wisdom, and subsequently of the union of Logos

and Wisdom in John 1.

Philo (20 b .c. e-50 c. e.), another

philosopher of importance, added significantly to the theological

underpinnings of Christianity. Philo used allegory to interpret Hebrew

religious traditions. In this manner he looked for hidden meaning in

the text and read back into it new interpretation (45). This method had

implications for Philo’s thoughts on Logos. Philo “fused Greek

philosophical concepts with Hebrew religious thought” (55), providing

more intellectual foundation for the acceptance of Christian writings

than was produced in the first and second centuries. Hillar believes

that Philo spent more time developing his ideas on Logos than on his

other intellectual interests.

For example, Philo defined Logos as

“utterance of God” and “divine mind” (56), “the agent of creation and

transcendent power” (57), “Universal bond and immanent reason” (60),

“the immanent Mediator” (62), and the “Angel of the Lord which is the

Revealer of God” (63).

In guiding the reader toward understanding the

development of thought leading to the trinity, Hillar elaborates

regarding the messianic tradition of the Jews in which eschatological

and apocalyptic themes were emphasized in Judaic writings, worship and

culture. The Jews believed God acts on behalf of the righteous of

Israel (102). Further, the ideas of messianic and apocalyptic

eschatology were carried through to Hellenistic Christian thought.

“Christianity” was first an early Jewish messianic movement (112).

Members were first identified as “Nazoraeans” before being called

“Christians” because their Messiah would be a Nazarene as stated in

Matthew 2:23 (114).

In the historical journey of discovery guided by

Hillar’s research, the reader is next given a thorough tour of the works

of Justin Martyr. Martyr was influenced by Numenius’ Middle Platonic

thought on the soul (148), and also by his thought on Logos as First God

and Second God (147). To Martyr belongs the distinction of being the

first church father to label the theological ideas of Pythagoras, the

Monad, Dyad and Harmony, as “triad”. This is significant because it was

the Latin layman, Tertullian, who finally translated “triad” to the

Latin trinitas, or “trinity”.

No comments:

Post a Comment