so...

https://www.stthom.edu/Faculty/Faculty-Directory.aqf?Faculty_ID=125859

Tenured!

He also is interested in Tai Chi, Eucharistic Adoration and Gregorian Chant and conflicts and harmonies between science and faith.

watch out.

the backbone of modern science indeed!

stunning actually.

So this is the example that Professor Louis Kauffman refers to for explaining relativity.

It is truly stunningly simple.

I thought it was more complicated than this!

And then the most famous equation of science is derived! Yes indeed.

Stunning.

And now we find the reverse logic:

Yes no need to really study the ORIGIN of the Pythagorean Theorem since we can just reverse engineer the natural numbers!

The harmonic mean of G/D'

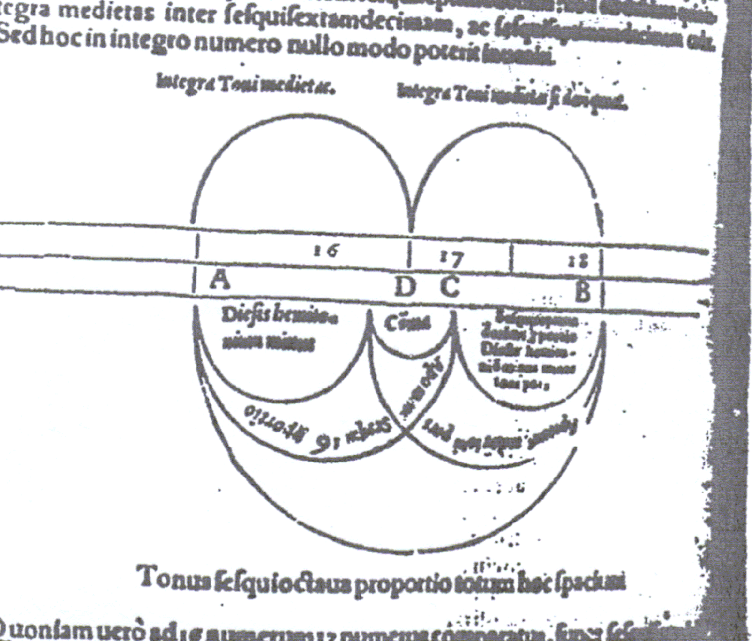

Finally, [by] the [power which is the opposite] of duplication, which tends towards the middle, . . [in particular, by the arithmetic and harmonic means] , . . . in the middle of 6 to 12, the ratios 2 : 3 and 3 : 4 come together.

https://sccn.ucsd.edu/~scott/MeansMeaningMusic_exTempore1981.html

So we know the Harmonic Mean is the Perfect Fourth but this physics teacher gets it WRONG. oops.

He states:

No wonder he got it wrong since he citers Fideler who is promoting the Pythagorean Liar of the Lyre from Archytas and Philolaus.

So the great noncommutative phase secret is LOST again! haha.

Plato then mentions that, "there are two means in every interval,"42 that is, both the harmonic and arithmetic means of 6 : 12 and of 6 : 18 are already present in the number system. For the arithmetic mean of 6 and 12 is 9, and of 6 and 18 is 12, while the harmonic mean of 6 and 12 is 8, and of 6 and 18 is 9.

So the harmonic mean is 2/3 is you Change the direction of the Octave - by going the opposite way! But that changes what the DENOMINATOR is for the ratio.

https://sci-hub.se/https://jstor.org/stable/4181963

That brings us to this article.

Apollonius of Tyana, a Pythagorean philosopher who lived in the first c. CE, is the subject of Philostratus' VA, composed in the early 3rd c. CE. Following the Pythagorean tradition, Apollonius takes a five-year vow of silence (VA 1.14). The differences between Pythagorean and Apollonian silence, however, have escaped notice, even in treatments of Apollonius' relationship to Pythagoreanism (Flinterman 2009). Pythagoras' disciples took a five-year vow of silence in order to listen to Pythagorean doctrine, which Pythagoras delivered from behind a veil so that his disciples could only hear but not see him (Iamblichus, Life of Pythagoras 17, Diogenes Laertius, Life of Pythagoras 8, cf. Montiglio 2000: 27-8). Apollonius behaves completely differently during his period of silence: he listens to no doctrines, but rather travels, communicating silently with many people. When people speak to him, he responds “with his eyes, his hands, or by the motions of his head” (VA 1.14). He quells a pantomime riot with a silent glance, and asks about a lawsuit with a gesture of his hand (VA 1.15). By learning to communicate with gestures and other body language, Apollonius learns to control his own movements as well as to interpret physical signs in the bodies of others (e.g. VA 7.42). He shares this physiognomic knowledge with the Indian wise men, who select their students by observation of their physical characteristics (VA 2.30).

I argue that Philostratus invites his readers to see Apollonius' silence as similar to the silence of pantomimes, who danced out the stories of classical myth and tragedy in silence. The immense popularity of pantomime in the Greek world in the late 2nd and early 3rd c. CE has been well studied (Hall 2013, Webb 2008, Hall and Wyles 2008, Lada-Richards 2007, Garelli 2007). Pantomime was a narrative dance, and the dancers communicated with their audiences by specific movements of their hands and feet. An epitaph for the pantomime Crispus from Herakleia from the 2nd/ 3rd c. CE describes “the whole world marveling at him gesturing with his hands” (SEG 31.1072). The resemblance of Apollonius to a pantomime has been observed fleetingly (Montiglio 2005: 220), but the implications of this have not yet been explored. Philostratus was neither the first nor the last to make this connection: Lucian's Lycinus says that he has heard someone say that the silence of the dancers “was symbolic of a Pythagorean tenet” (Lucian, On Pantomime 70), and in a discussion of various philosopher-dancers (including the dancing Socrates) Athenaeus mentions a pantomime, Memphis, who “explains the nature of the Pythagorean system, expounding in silent mimicry all its doctrines to us more clearly than they who profess to teach eloquence” (Athenaeus, Sophists at Dinner, I.20d). These passages suggest that Philostratus may have been responding not only to an element of popular culture in his use of pantomime in the VA, but also to a specific association between Pythagorean silence and the silence of pantomimes.

Very fascinating indeed!

https://www.stichting-pythagoras.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Newsletter-21.pdf

She's at my alma mater - UW-Madison.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C2brjVcogKw

https://twitter.com/maliskotheim?lang=en

No comments:

Post a Comment