"We are almost hardwired to appreciate music aesthetically," Karageorghis says. People's emotional response to music is visceral: It is, in part, ingrained in some of the oldest regions of the brain in terms of evolutionary history, rather than in the large wrinkly human cortex that evolved more recently. One patient—a woman known in the research literature as I. R.—exemplifies this primal response. I. R. has lesions to her auditory cortices, the regions of the cortex that process sound. When I. R. hears the normal version of a song and a horribly detuned version, she cannot tell the difference, explains Jessica Grahn, a cognitive neuroscientist who studies music at Western University's Brain and Mind Institute in Ontario. But when I. R. hears a happy song and a sad song, she immediately distinguishes them from one another.So we know that the study of the (Mafas) tribe in Africa that had not hear Western music (googlebooks) - they also recognized happy, sad and scary music (i.e. Major mode, Minor mode and diminished chord mode).

So that would be the "diminished" scale mode.

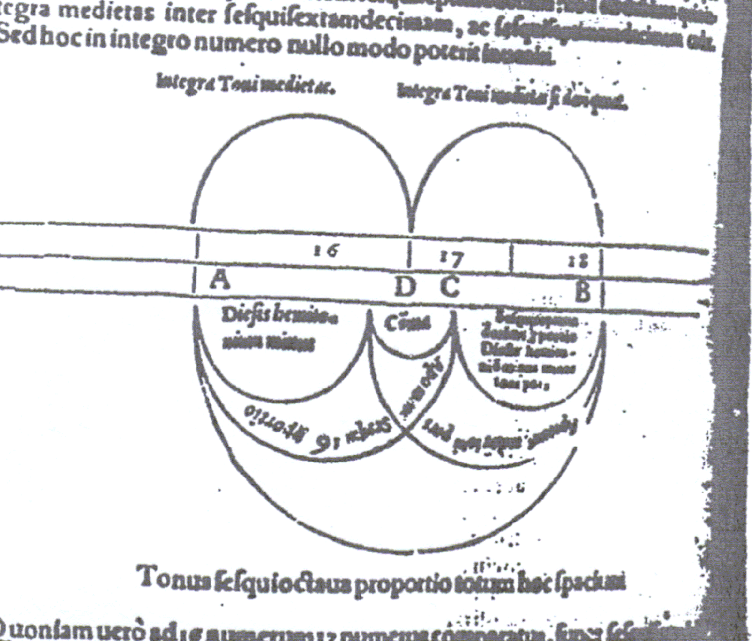

But the point is that the tuning does not have to be precise - rather it's the over all relation of the intervals as a scale mode of the octave.

This is quite fascinating - since the ancient scales did not have equal-tempered tuning for vertical harmony but most likely the modes allowed for a greater depth of emotional subtlety and expression.

the paralimbic regions involved in affective responsesJesse Prinz on emotional morality and attentional resonance vid

So that book I link above states that case study I.R. can NOT recognize dissonance even though dissonance is processed on a subcortical deep brain level.

Rather the results suggest that emotional responses to dissonance are mediated via an obligatory cortical perceptual relay.but this could not be confirmed since she could not be given an fMRI due to metal clips in her brain.

The Evolution of Emotional Communication: From Sounds in Nonhuman Mammals to Speech and Music in Man

Contour in both music and speech is defined by the direction of pitch changes, but not by specific pitch relationships. Contour is especially relevant for speech, since direction of intonation can change linguistic meaning (e.g., question versus statement, or rising versus falling tones in Mandarin). But contour also plays a fundamental role in music perception: cognitive studies have shown that contour information is more perceptually salient (Figure 3) and more easily remembered, whereas specific intervals take more time to encode [10]. Infants detect contour but not interval information [11], implying that it is a more basic process that develops early or is innate. The neural correlates of contour and scale processing also appear to differ [12],[13]. Taken together, these findings suggest that perhaps the coarse pitch processing related to contour might represent one mechanism used for both speech and music, whereas the precise encoding and production required for musical scale information might be a separate mechanism, perhaps even one that emerged later in phylogeny.

So the music and tonal language based on emotions - appear to have different processing.

evidence also exists supporting the notion of a shared neural substrate for the processing of melody in speech and music. For example, there have been a number of studies of patients with documented lesions that result in music processing deficits that have reported parallel difficulties in the perception of speech prosody [18],[19]. Such patterns of partially shared but dissociable processing mechanisms fit well with our hypothesis of dual processing mechanisms for pitch perception. Functional imaging studies show evidence both for segregation and overlap in the recruitment of cortical circuits for perception of speech and of tonal patterns [20]–[23], but the commonalities may be more apparent than real.

but greater reliance on right-hemisphere structures during singing compared to speaking [29]. Imaging studies of trained singers [30],[31] indicate that singing involves specialized contributions of auditory cortical regions, along with somatosensory and motor-related structures, suggesting that singing makes particular demands on auditory-vocal integration mechanisms related to the high level of pitch accuracy required for singing in tune, which is less relevant for speech.

there seem to be two mechanisms, one focused on contour, which may overlap across domains, and another, perhaps specific to music, involving more accurate pitch encoding and production.Seals - our common ancestral traits

Collection of slapping data will enable to test hypotheses postulating group and mating displays as necessary evolutionary steps toward human musicality (Fitch, 2009; Merker et al., 2009). In fact, if harbor seals' slaps show strong temporal interdependence between individuals, successful entrainment experiments in this species would support the hypothesis that rhythm may have evolved in humans as by-product of temporally-intertwined group displays (Merker et al., 2009).rhythm

We found that, when immediate feedback about the timing of each movement is provided, monkeys can predictively entrain to an isochronous beat, generating tapping movements in anticipation of the metronome pulse. This ability also generalized to a novel untrained tempo. Notably, macaques can modify their tapping tempo by predicting the beat changes of accelerating and decelerating visual metronomes in a manner similar to humans. Our findings support the notion that nonhuman primates share with humans the ability of temporal anticipation during tapping to isochronous and smoothly changing sequences of stimuli.Dale Purves on why a few human music scales are universal lecture

Purves summarizes evidence that the intervals defining Western and other scales are those with the greatest collective similarity to the human voice; that major and minor scales are heard as happy or sad because they mimic the subdued and excited speech of these emotional states; and that the character of a culture’s speech influences the tonal palette of its traditional music.book 2017

articleGoffinet’s complaints (1) about our vocal similarity hypothesis (2) are unwarranted on both practical and theoretical grounds.First, the issue of tuning is a red herring. We used standard just intonation intervals to evaluate the consonance of chords because their role in music across historical and cultural boundaries is foundational (3). We limited the chords tested to combinations of the 12 intervals of the chromatic scale for practical reasons: additional ratios and/or tuning systems would have increased the chords that had to be evaluated to an unreasonable number.More generally, our results are unlikely to depend on a particular tuning system. The popular chords in our study correspond to those frequently used in popular (equally tempered) music, reflecting the fact that people tolerate substantial tuning variation in practice (4). Furthermore, the harmonic similarity metric we use can be adapted to accommodate tuning variation by introducing a tolerance window for judgments of harmonic overlap (2).Regarding the tritone, we selected the simplest possible ratio (7:5). Had we chosen a more complex ratio, our predictions would likely have improved. Because the 7:5 ratio has a relatively high harmonic similarity score (31.4%), chords containing tritones were often predicted to be more consonant than actually perceived. Mistakes of this kind accounted for 46% of the errors in our study [see supporting information of our report (2)].Second, limiting the analysis to pairs of chords exhibiting significant differences in consonance does not inflate the accuracy of vocal similarity; it excludes noise due to differences that people do not reliably perceive. Because consonance is a perceptual phenomenon, what people hear must be the basis for any analysis.Third, roughness models do not explain consonance (5). The idea that the human attraction to tone combinations in melody and harmony is determined by the absence of neural “irritation” is nonsensical. Roughness is inversely correlated with harmonic similarity, and thus with consonance. However, when roughness and harmonic similarity are dissociated, only the latter accords with consonance (6, 7).Fourth, the assertion that our metrics do not assess vocal similarity because they do not consider formants is incorrect. Harmonic spectra are a universal property of laryngeal vocalization, and their biological relevance principally derives from conspecific communication. Thus, any metric that captures harmonic structure over the range of biological vocalization measures vocal similarity. We have previously investigated formant information, with results that are less predictive of consonance than harmonic relationships (8). Similarly, differences in timbre have little effect on consonance, provided that spectra are harmonic.The vocal similarity hypothesis is motivated by the recognition that music is a biological phenomenon, perceived by neural circuitry that has been shaped by the requirements of vocal communication. Although the basis of consonance remains controversial (9, 10), our study (2) adds to empirical evidence that its central importance in music is founded on the biology of auditory–vocal communication, as are many other musical phenomena [see refs. 24–31 in our report (2)]. The criticisms Goffinet (1) offers refute neither the accuracy of our results, nor the importance of the biological framework on which they depend.

for reasons of biological advantage, human tonal preferences can be understood in terms of the spectral similarity of tone combinations to harmonic human vocalizations.https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01543/full

male budgerigars spent more time with arrthymic stimuli, and female budgerigars spent more time with rhythmic stimuli. Our results support the idea that rhythmic information is interesting to budgerigars. We suggest that future investigations into the temporal characteristics of naturalistic social behaviors in budgerigars, such as courtship vocalizations and head-bobbing displays, may help explain the sex difference we observed.music as evolution

And fifth, the universal propensity of humans to gather occasionally to sing and dance together in a group, which suggests a motivational basis endemic to our biology. We end by considering the evolutionary context within which these constraints had to be met in the genesis of human musicality.So in the Q and A - an "acoustician" physicist CONFUSES the harmonics series with the equal-tempered tuning!!

There's along history theorizing about the Harmonic series, .... the ecological importance of the harmonic series. The consonance intervals are closely mimicked in the harmonic series....

Contrary to the claim of the questioner:

If you JUST use the Harmonic series you don't get the chromatic scale.

Question: You do get the chromatic scale from the harmonic series - If you tune a series of Perfect Fifths, after about 12 tunings ...you end up PRETTY WELL back up where you were.

Professor Dale Purves: That's true? Is that plausible? What biological foundation does the Pythagorean Tuning....

The question IGNORES the fact that PHASE is the difference that creates the MODES as emotional meaning!! The question IGNORES the fact that the Harmonic series is NOT the same as the chromatic scale - due to the Ghost or Phantom Tonic of the PErfect Fourth, as I've pointed out. Time-frequency uncertainty is the physical truth of reality of the Harmonic Series!

Professor Dale Purves: I guess I disagree with you that the chromatic scale comes readily out of the harmonic series, in a way that makes biological sense.

answer: well there would be thousands of theorists that would disagree with you. You could certainly get the diatonic scale.

Professor Purves: Diatonic scale is just a subset.... Even if you say that, what is the biological significance of that. In speech it's ALL about biology! You got the Chromatic scale in speech - puts you in a biological framework, not a physical framework, where you're talking about the Harmonic Series.

Questioner: ONe could argue that the Physical principles are even MORE fundamental than the biological principles. So if you look at Francis Crick for example....one is evolution, the other is non-equilibrium pattern formation....

Professor Dale Purves: The PHysics of the world is UNAVAILABLE to the visual system. It's just not possible to get every metric of the real world parameters in terms of photons. And I would said it's going to be the SAME in Audition - the physics is going to be BEYOND the pale of what the auditory system can access.

Dear Professor Dale Purves: Regarding your UCMerced lecture on

youtube with the challenger re: the Harmonic Series, there is a secret

to music theory that scientists often miss. So he was claiming the

chromatic scale could derived from the Harmonic Series and you disagreed

with this - correctly. The reason you are correct is that the Perfect

Fourth is noncommutative phase to the Perfect Fifth and this basic fact

was covered up to create the origin of the Greek Miracle as irrational

magnitude symmetric commutative mathematical physics.

So Alain Connes, the Fields Medal math professor, has a lecture on youtube on music theory and noncommutative geometry, confirming that this secret of music theory actually enables the "formal language" for a unified field science. So in nonwestern music - as you correctly point out - the sad/happy/scary modes are universal - as expressed in language also. There is a deeper meaning to this also as - the photon parameter that you mention is also based on this noncommutative time-frequency phase, as Louis de Broglie discovered. So I have been corresponding with Nobel physicist Brian Josephson about this and now he is focused on cymatics.

But I agree with you that the emotional biological context is key - and as you know, the older language is, then the more musical it is. I have researched this topic for 30 years - and I did a master's degree studying this topic, before I had realized the noncommutative phase secret. So I'm just pointing out - the person who claimed there were thousands of studies about the harmonic series creating the chromatic music scale - yes that is only by assuming a Western symmetric math bias that covers up this deeper noncommutative phase truth of math. So until now Western math has relied on the symmetric logic - this is explained by Alain Connes.

So in terms of biology - I did my master's thesis on music theory and "radical ecology" - in 2000 at University of Minnesota - the title is called "Epicenters of Justice: Music theory, radical ecology and sound-current nondualism." So again I had made errors since I did not understand this noncommutative phase secret of music theory - but I was close. So by scientists not understanding the noncommutative phase secret - that means it also changes how we define entropy in physics in relation to biology as well.

I have details on my blog http://elixirfield.blogspot.com and http://ecoechoinvasives.blogspot.com So in music theory this is called the "Ghost Tonic" about the noncommutative phase of the Perfect Fourth - it was covered up by Philolaus when he literally "flipped" his lyre around to create a symmetric double octave - thereby converting the chromatic scale into a logarithmic symmetric equal-tempered scale. So then the Harmonic Series already assumes this logarithmic math! Math professor Luigi Borzacchini has a great article on this "cognitive bias" at the foundation of science - from music theory - on "the continuum and incommensurability." I've corresponded with him as well - starting in 2001.

So Alain Connes, the Fields Medal math professor, has a lecture on youtube on music theory and noncommutative geometry, confirming that this secret of music theory actually enables the "formal language" for a unified field science. So in nonwestern music - as you correctly point out - the sad/happy/scary modes are universal - as expressed in language also. There is a deeper meaning to this also as - the photon parameter that you mention is also based on this noncommutative time-frequency phase, as Louis de Broglie discovered. So I have been corresponding with Nobel physicist Brian Josephson about this and now he is focused on cymatics.

But I agree with you that the emotional biological context is key - and as you know, the older language is, then the more musical it is. I have researched this topic for 30 years - and I did a master's degree studying this topic, before I had realized the noncommutative phase secret. So I'm just pointing out - the person who claimed there were thousands of studies about the harmonic series creating the chromatic music scale - yes that is only by assuming a Western symmetric math bias that covers up this deeper noncommutative phase truth of math. So until now Western math has relied on the symmetric logic - this is explained by Alain Connes.

So in terms of biology - I did my master's thesis on music theory and "radical ecology" - in 2000 at University of Minnesota - the title is called "Epicenters of Justice: Music theory, radical ecology and sound-current nondualism." So again I had made errors since I did not understand this noncommutative phase secret of music theory - but I was close. So by scientists not understanding the noncommutative phase secret - that means it also changes how we define entropy in physics in relation to biology as well.

I have details on my blog http://elixirfield.blogspot.com and http://ecoechoinvasives.blogspot.com So in music theory this is called the "Ghost Tonic" about the noncommutative phase of the Perfect Fourth - it was covered up by Philolaus when he literally "flipped" his lyre around to create a symmetric double octave - thereby converting the chromatic scale into a logarithmic symmetric equal-tempered scale. So then the Harmonic Series already assumes this logarithmic math! Math professor Luigi Borzacchini has a great article on this "cognitive bias" at the foundation of science - from music theory - on "the continuum and incommensurability." I've corresponded with him as well - starting in 2001.

Take care and let me know if you want more info on this subject, comments or questions, etc.

Thanks for your great research!

yes Western equal-tempered tuning has locked us into a circular tautological emotional deadlock of fear-anger-sex - and with the pancreas/spleen the emotion is worry - over-thinking. I once composed a Fugue similar to that composition - only it was for a Mayan flute whistle and a Moog keyboard. I wrote a paper on the fugue and then I composed the fugue. Then I recorded the fugue - but I had a new 4trac and I didn't synchronize the voicing correctly. So the fugue "decomposed" itself as it went along and I called it Troll Dance. That was in 1990. Then one of the advisors was David Muesham. And so I just met him as he was with the music professor - and they passed me on that Level 1 project for Hampshire College. So then almost 30 years later I was reading an article on music and traditional chinese medicine healing. I'll get you the article. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4010966/ Life Rhythm as a Symphony of Oscillatory Patterns: Electromagnetic Energy and Sound Vibration Modulates Gene Expression for Biological Signaling and Healing So then the author's name looked familiar and I looked him up and seeing his photo - I realized it must be the same person. And then I discovered he had trained in yoga in India but he was a physics major. So I emailed him and he remembered my Troll dance fugue and we corresponded about our mutual research interests. And so now https://www.chi.is/resource/emfhistory/ he works for this -

No comments:

Post a Comment